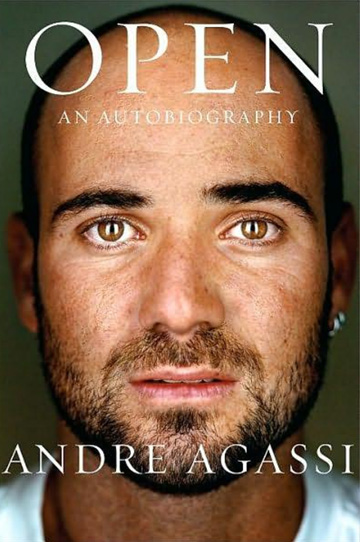

Open

November 27, 2009 | The Barnes & Noble Review

Before reading a single page of Andre Agassi’s autobiography, Open, I determined to evaluate it according to the standards established in a lovely little essay called “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart,” by David Foster Wallace. Austin was a tennis star in the 1970s whose memoir Wallace, an exuberant observer of the game, agreed to review for a newspaper in 1994. He had high hopes, because on the court Austin was “prodigious, beautiful, and inspiring” — a true artist who displayed “a grace that for most of us remains abstract and immanent.” But he was disappointed to find that her memoir was terrible: insipid, cliché-ridden, and almost completely lacking in insight, or even compound sentences.

Maybe, Wallace observed, he was foolish to “expect people who are geniuses as athletes to be geniuses also as speakers and writers, to be articulate, perceptive, truthful, profound.” Maybe we keep buying ghost-written sports memoirs in the vain search for a superstar who embodies both types of brilliance, someone who not only has the golden touch but can explain what it feels like to have it. The most distressing revelation for Wallace was not that Tracy Austin lacked an expressive intellect but that, ironically, it may have been precisely this lacuna that allowed her to succeed in the relentless psychological siege that is competitive tennis. After all, by his own admission the heady Wallace blew many a junior match by thinking, rather than just playing.

I had good reason to hope that Agassi might do better. Throughout his 21-year career, he was consistently one of the most articulate and thoughtful interviews on the professional tennis tour. His brutal de- and reconstruction of not just his body but his game and persona — from flabby, cocky rebel to sculpted, focused champion; from “Image Is Everything” to pure substance — suggested introspection and self-awareness. Most notably, his tearful farewell upon retiring as the elder statesman of professional tennis at the 2006 U.S. Open was the most remarkable speech I have ever heard given by an athlete.

The speech was not only moving; it also offered a lesson in collective expectations about the thoughtfulness of our athlete-heroes. The crowd at Arthur Ashe Stadium almost refused to let the guy speak, as if they couldn’t bear to hear him flub it — until they realized that he could speak eloquently, at which point they hushed. They wanted to remember Agassi’s audacious return of serve and blink-snap reflexes; they feared that these memories would be tarnished by a rambling and dull goodbye. Can you blame them for fearing this might happen? No less a poet on court than John McEnroe — all finesse and touch at the net, despite his famous temper — can be heard on TV every summer incanting that this or that player must “find another gear” or “dig deeper” in order to win. McEnroe has uttered these clichés hundreds of times, and their ability to illuminate does not increase with repetition.

Agassi raises hopes that he’ll avoid such boilerplate on the first page of Open, where he declares, in a startling line redolent of Graham Greene’s opening scene in The End of the Affair, that he hates tennis and always has. I had not known or expected this. It certainly increased the chances that Agassi would have an interesting story to tell. His father, the King Kong of sports dads, literally taped a racquet to his hand and encouraged him to swing it at a mobile of balls that dangled above his crib. Agassi senior also made his son spend every free hour of his childhood on court and smashed his runner-up trophies. Few people would enjoy tennis after such an upbringing.

But despite what he calls his hate/love relationship to the sport, Agassi played an extraordinary and transformative game from the moment he turned pro at age 16. He did not invent topspin, oversized racquets, the two-handed backhand, or a game played mainly from the baseline, but he popularized these elements to a generation of kids who wore denim shorts over neon-pink hot pants to summer tennis camp. Agassi’s most distinctive tactic came directly from on-court drills with his father, who fired a ball machine called “the Dragon” at his son from a high angle, forcing Agassi to hit the ball on the rise — immediately after its bounce, rather than after it bounced and described an arc.

This skill — the product not just of practice but also extraordinary hand-eye coordination — allowed Agassi to rob opponents like Pete Sampras of their most powerful weapon: their serves. Watching Agassi stand inside the baseline and hit a perfectly timed, walk-off winner against a 130-mile-per-hour-serve is a thrilling experience: it defies all expectations about how the game works and is the psychological and dramatic equivalent of a sprinter spinning around and finishing the last 25 meters backward. When Agassi added conditioning, a bigger serve, and net play to his arsenal, he became a truly formidable opponent, winning eight Grand Slams and rising several times to the No. 1 spot in the rankings.

Although Open is not beautifully written, Agassi’s reflections on internalizing his father’s vicious drive — and on realizing that he didn’t have to love tennis in order to need to play it — are poignant and insightful. Better yet are his thoughts about the “hysterical serenity” of victory, which never feels as good as a loss does bad, and his discovery of purpose on the court when he began putting his winnings to philanthropic use. Above all, Agassi describes the loneliness of a sport that places two players 80 feet apart for as long as five hours at a stretch without teammates or coaches. It is loneliness, he explains, that leads tennis players to talk to themselves constantly, frequently out loud, battling with momentum, expectations, and especially self-doubt. (You’ll notice that the peerless Roger Federer rarely says a word during a match.) Agassi suggests that his own career rose from the doldrums in the late 1990s precisely because he learned to stop thinking while he played — he must simply feel, and hit. In what he calls the best match of his life — an extraordinary quarter-final victory over James Blake at the 2005 U.S. Open– Agassi describes reaching a “mindless state” in which fear of losing, or missing, or the cruel sportswriters, finally receded and he simply swung the racket.

These are the highlights. The bulk of the book is chronology, not reflection. Open contains its share of vapid observations: for instance, Agassi told himself he was upset while separating from his first wife, Brooke Shields, “because you hate losing. And divorce is one tough loss.” But the book is also filled with startling candor: Agassi used crystal meth and lied about it to tennis officials. He threw a match or two. His acknowledgments page is, remarkably, one long, kind paean to his ghostwriter, who refused to be named on the cover. Most surprisingly — and touchingly, for readers who grew up admiring the way Agassi’s luxuriant mane swayed manfully as he played — he reveals that he wore a hairpiece, helplessly embarrassed by his premature baldness. Wallace was right that we will always hope for an articulate, demonstrative intelligence in the athletes we admire. But a bit of that plus generosity, a good heart, and unvarnished honesty is equally becoming.