Another Frenchman Assesses our Democracy

January 29, 2006 | San Francisco Chronicle

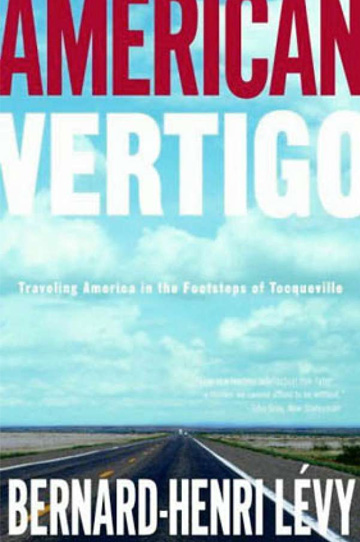

In the opening of “American Vertigo,” Bernard-Henri Lévy (or BHL, as he is commonly known) warns that his book should not be viewed as a reply or addition to Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1840 masterwork, “Democracy in America.” He’s right. The latter was a Frenchman’s explication of the unique form of American government — especially compared with European monarchies — and of the character of a people with the constitution (so to speak) to make such a system work. The former is a Frenchman’s travelogue, a come-with-me journey of meetings and happenings, of visits to Midwestern diners and Southern mega-churches, with the author’s ruminations and digressions filling out the gaps. Lévy wrote while he traveled. Tocqueville first traveled, then wrote. Lévy wrote about this American and that one. Tocqueville wrote about America, full stop.

Proviso notwithstanding, Lévy’s book cries out for comparisons to his predecessor’s — the subtitle, after all, is “Traveling America in the Footsteps of Tocqueville.” And anyway, such caveats really are pro forma these days. One can’t waltz around claiming to have written “Madame Bovary Deux.”

Many will read “American Vertigo” because of BHL, not Tocqueville. Lévy is a glamorous and wealthy Left Bank intellectual, a fixture of the continental gossip rags and an occasional emissary for the French government (he recently served as President Jacques Chirac’s envoy to Afghanistan). His critics would add to that litany a grandstander and a self-promoter: “God is dead but my hair is perfect,” is just one tagline that the superstar philosopher can’t seem to shake. On the page, the ego does come through, and his more grandiloquent habits, such as the odd pagelong sentence, will put off some readers.

But even though he is a bit ridiculous, Lévy is not unserious. His exploration of America’s penal system — the original purpose of Tocqueville’s visit — is provocative and worth reading, progressing from the brutal conditions of Rikers Island to the ultimate separation of Alcatraz to the trend of privatizing corrections, and ending, inevitably, at Guantanamo Bay. To Lévy, who bristles at knee-jerk anti-Americanism, this newest prison is not only unacceptable, but it is also of a piece with the penal system as a whole in how it fetishizes banishment and prioritizes badly — for instance, in the way Guantanamo tortures its prisoners and somehow thinks it can right the balance by scrupulously caring for their “spiritual needs.”

The book also offers a new perspective on American memory. Lévy is confounded by Mount Rushmore: Built by a Klansman on land expropriated from American Indians, it stands majestically next to a pathetic memorial at nearby Wounded Knee. After visiting Cooperstown, N.Y., he contemplates Americans’ strange compulsion to memorialize everything in museums, and is refreshed by the living history — preserved in that most European of foundations, the city — that he finds in Savannah, Ga. He also sensitively confronts our willful blindness, as when we cling to Camelot despite knowing that Kennedy was a physically broken womanizer.

Lévy can be a writer of enormous power and vitality, and more than a few times he perfectly captures a piece of American life. He writes that black delegates to an evangelical convention in Memphis were “formal, deadly serious, walking as if in a procession, at once rivals and accomplices in their admirable wish to offer the Almighty the spectacle of their gold and finery.” Of the Mayo Clinic he writes, “given that here lies one of the core issues of the country, one of its bleeding wounds; given that reform of the public-health system is the most difficult challenge America will have to meet over the next few years — given all that, I choose … to buy into the medical legend. Long live the Mayo Clinic. Long live its consulting physicians. Long live its philosophy of recruiting from within and its so proudly nonlucrative aims. Long live its culture of excellence and its practice of achievement.” And Los Angeles is a “burgeoning city that goes on indefinitely, interminably stammering, a huge slow animal, lazy but silently out of control.”

The precision with which Lévy frequently hits the mark makes all the more frustrating those instances where he misses it. He neglects the culture of business and enterprise that is such a fundamental part of American identity. He strays too often into scoring points against rival thinkers. And why any writer today would spill so much ink on Monica Lewinsky is utterly beyond this reviewer. This last point is symptomatic: In too many ways Lévy’s discussion centers on headlines (Hillary Clinton’s chances in 2008, Darwin versus the “intelligent design” creationists) rather than the broader, structural questions that have made Tocqueville’s work endure. The epilogue’s spirited defense of the country from America bashers in Europe is an exception, but he has already made many of these points elsewhere. The result is a book that is alternately exasperating and thrilling, turn-off and spot-on. Not unlike its subject.