Radical Streak

May 1, 2009 | Washington Monthly

Leonard Bernstein took a lot of flak for his antics on the podium. Patrons of the New York Philharmonic at mid-century were either delighted or appalled to catch a glimpse of the “Lenny leap,” an uncouth maneuver that found the enthusiastic maestro a good foot in the air before a momentous downbeat. A newspaper critic complained that when Bernstein conducted, he spent most of his time not keeping time or cueing musicians but “fencing, hula-dancing and calling upon the heavens to witness his agonies.” Once, when he was rehearsing the finale of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony, which calls for a pianissimo so soft that it fades into nothingness, the Tanglewood chorus kept singing a little too loudly. Bernstein, who was Mahler’s greatest champion and had to have it just right, lay down on the podium like some hippie chained to a tree and refused to budge until they sang it softer. Here he was, the great icon of twentieth-century American classical music, taking it to the streets, sixties-style. The year was 1953.

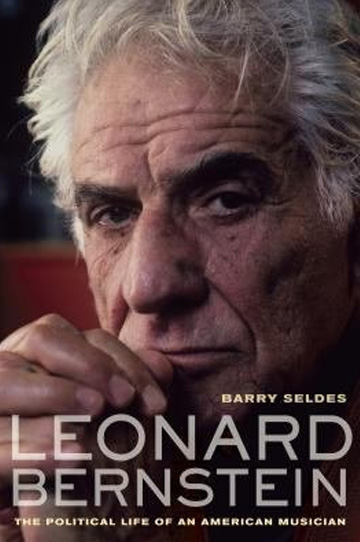

If anyone were likely to hold a conductin, it was Bernstein, a civil rights marcher, Zionist, gay rights activist, no-nukes partisan, antifascist, sexual liberationist, cowboy boot wearer, and inveterate attender of fund-raisers, speaker at rallies, and signer of petitions. A new book discussing his political achievements and indignities has just arrived: Barry Seldes’s Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician. Seldes believes that politics, rather than Judaism, American identity, or a unique aesthetic vision, was the animating force of Bernstein’s creative life. Regardless of the merits of this claim (about which more directly), it must be said that such a work could start an unfortunate trend. When we are subjected to books on the political activism of Susan Sarandon, Tim Robbins, and George Clooney—Oceans of Third-World Debt, maybe?—we must first remember, before joining hands and jumping off bridges, to write Seldes a strongly worded letter.

Long before Sean Penn threw his arm around Hugo Chávez, Bernstein was engaged in radical chic. Indeed, he was its modern avatar: the writer Tom Wolfe coined the term in a scorching New York magazine article about a Black Panther fundraiser held at Bernstein’s Park Avenue apartment in 1970. There the maestro was unfortunately overheard by Wolfe and several other reporters to reply to “Field Marshal” Donald Cox’s injunction to “take the means of production and put them in the hands of the people” by saying, “I dig absolutely.” Partisans contend that Bernstein was actually being a smartass: Cox had ended his own sentence with “dig?” and Bernstein responded in kind. In any case, the press portrayed him as an elegant slummer, and the affair took years to live down.

But Bernstein was no Hanoi Jane. That party was by far the most notorious of his political outings, and even if he lent his name to many causes and spoke out frequently, he spent most of his time conducting, composing, seducing, and horsing around at the piano with friends. A bit of rabble-rousing actually lends color to such a titan of the culture; we’d even be a little disappointed if his bullhorn was never switched on. Still, Bernstein’s business was music, not politics, and Seldes’s attempt to reread his professional and creative achievements through a political lens ought to be approached skeptically.

Seldes contributes two things to our understanding of Bernstein’s life and art: first, new archival findings about the FBI’s monitoring of Bernstein’s activities; and second, an argument about the effect of a stifling political culture on his creative output. Bernstein was blacklisted by CBS and the U.S. State Department between 1950 and 1954, and the FBI kept track of him for years afterward in hopes of springing a perjury charge for his denial of communist sympathies. He was never indicted, and, unlike many of his contemporaries, he wasn’t called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. But he wrung his hands while waiting for an important passport renewal in 1953, and helped himself out of trouble by signing an inane affidavit confirming his patriotism. Seldes portrays these events as devastating—the passport imbroglio created a “living hell,” he writes—but doesn’t provide much evidence that Bernstein really thought so. In fact, Bernstein’s biographer Humphrey Burton persuasively recounts the passport ordeal as more of a headache than anything else, with Bernstein gushing about the cleverness of his lawyer, “an old Commie- chaser,” and saying that “it was worth the whole ghastly and humiliating experience just to know him.”

These episodes indeed add to our understanding of Bernstein’s life and times, but Seldes undercuts their significance by pointing out that Bernstein knew little of the FBI’s activities, which suggests that they couldn’t have troubled him much. The author also portrays the 1950s as an insular time that Bernstein soon forgot, “as if the years of repression had never happened.” Why, then, do they matter so much? The notion that Bernstein was heavily influenced by political troubles in the 1950s is questionable for another reason as well. His major compositions during that period—the opera Trouble in Tahiti; the musicals Wonderful Town, Candide, and West Side Story; the concertoesque Serenade (After Plato’s Symposium); and the Second Symphony, The Age of Anxiety—are apolitical thematically, with the exception of an anti-McCarthy jibe or two in Candide. (The latter four works are also perhaps Bernstein’s best.) Surely a composer who was suffering a living hell because of state repression would have written more music about the experience.

This leads to Seldes’s other contribution: the novel thesis that Bernstein never produced his elusive masterwork late in life because “the dynamics of the American political culture … may have stultified or helped stultify his ambitions.” In particular, Seldes points to Ronald Reagan’s ascendance as a sort of last straw; when Reagan won the presidency in 1980, “the potential source of inspiration for Bernstein’s long-sought masterpiece, pointing audiences to a revival of their long-buried progressive ideas, disappeared.” This argument—blame it on the Gipper!—is necessarily the product of speculation, and it has other drawbacks, too. Start with its premise, that Bernstein never produced a masterwork: what about West Side Story? And if Bernstein’s pen dried up during the second half of his life, the more plausible explanations are that he exhausted himself by accepting too many conducting engagements—a point borne out repeatedly in his correspondence—and that, like many an artist, he produced his best work early on.

Still, Seldes may be on to something in arguing that Bernstein searched in vain for a political muse as the country shifted to the right. He was a thoroughly political animal, and during Reagan’s morning in America found himself in an inhospitable wilderness. Where the author goes wrong is in assuming that political inspiration could have helped Bernstein write a masterpiece. On the contrary, we should be thankful that he did more conducting than composing during his golden years, for his weakest works are consistently his late-term, preachy, overtly political extravaganzas, like the Third Symphony, Kaddish (1963), the hit-or-miss Mass (1971), and, most of all, the disastrous 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (1976), which sought “to survey the practice of slavery and racism over the course of American history by focusing on the reflections of a black couple that works in the White House for assorted presidents, from Washington through Theodore Roosevelt.” How’s that for an evening at the theater?

Bernstein’s political outrage was not only moralistic, it may have also been too diffuse and unfocused to find a suitable outlet in music. The most poignant and successful political works take precise aim and can hit their target for that reason, like Dmitri Shostakovitch’s Tenth Symphony, a passionate tirade against Stalin and an elegy for all lost under him. Bernstein, by contrast, broadly deplored not just racism but “a society consumed with fads and consumer gluttony that was unready to understand or deal with the destitution of the American inner city and was largely uncritical of the latest of twentieth-century catastrophes, the war in Vietnam.” Inequality, consumerism, poverty, war: imagine trying to give expression to such a comprehensive despair of the modern predicament in an abstract and symbolic medium like a symphony. It is telling that one of Bernstein’s only successful pieces of overtly political music was the plaintive, anti–Vietnam War song “So Pretty,” which, rather than cataloging the world’s problems, focuses simply and elegantly on one of them, and does so poetically rather than didactically. If diagnosing every political injustice became Bernstein’s artistic mission, then it is little wonder that he failed.

But he was not entirely unsuccessful as a political actor. In fact, his greatest political achievement was not to diagnose, but to cure: to champion classical music as a vital cultural institution worthy of preservation and celebration. He accomplished this not just in his famous Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1973, his pre-concert talks, or his Young People’s Concerts, but also through sheer enthusiasm: those histrionics on the podium may have offended the well-heeled concert-box set, but they thrilled the masses. Under his glamorous baton, the classics were exciting and passionate once more. Bernstein also let the music take him where it would, which in itself was a sort of ecumenical statement about the power of music to heal and transcend. Hence his devotion to the previously unfashionable symphonies of his fellow Jew Mahler; his provocative decision to hold concerts in Germany in the late 1940s, when other conductors were boycotting the post-Reich regime; and his refusal to stop performing Wagner even though it deeply troubled him that he loved an anti-Semite’s music. If Bernstein is to be remembered for political activism, let it be for these universalist gestures. Better yet, let him be remembered for the beautiful music he made.