The Worst Job in the World

March 20, 2017 | Washington Monthly

In 1981, the Atlantic Monthly published a devastating critique of supply-side economics called “The Education of David Stockman.” The article was a major embarrassment for the Reagan administration: Stockman was the president’s budget director, and had publicly undermined the theory and numbers behind Reagan’s entire economic program. The cover of the magazine even featured a photograph of the wayward technocrat. Reagan’s chief of staff, James A. Baker III, called Stockman into his White House office for a chat, and put an end to his freelancing:

My friend, I want you to listen up good. Your ass is in a sling. All of the rest of them want you shit-canned right now. Immediately. This afternoon. If it weren’t for me, you’d be a goner already. . . . You’re going to have lunch with the president. The menu is humble pie. You’re going to eat every last motherfucking spoonful of it.

The scene is the classic depiction of a White House chief of staff: furious, profane, demanding of loyalty as he stands tall over every member of the executive branch save one. Hollywood loves such encounters. The most memorable portrayal of the chief of staff on the small screen, The West Wing, features scores of them, including in the show’s second episode, when Leo McGarry dresses down a surly vice president. In House of Cards, Chief of Staff Doug Stamper need only remove his glasses and thrust out his magnificent chin to get results. Failing that, he chokes disobedient underlings half to death.

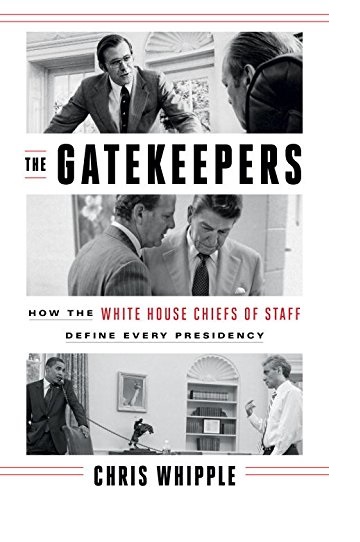

Baker clearly had to ring Stockman’s bell. Yet as the Emmy Award–winning writer and producer Chris Whipple shows in The Gatekeepers, his illuminating history of the office of chief of staff, an effective chief mustn’t overplay the drill sergeant card. Javelin catcher, the Abominable No Man, Undersecretary for Go Fuck Yourself—these colorful honorifics lampoon a quality that is essential in the right dose but ineffective when overdone.

And some have overdone it, relishing power and behaving imperially until they were brought down by their own troops. Baker’s successor, Don Regan, hung up the phone on the wrong first lady and found himself out on his ear. George H. W. Bush’s insufferable first chief of staff, John Sununu, boasted after screaming at a room of people that they would go back to their offices and marvel at how tough he was. His deputy disagreed: “They’re going to go back to their offices and tell everyone, ‘Sununu is a fucking asshole!’ ”

On the other hand, too little backbone creates its own problems. Bush’s second chief of staff, Sam Skinner, was overwhelmed by his responsibilities in what he called “the worst job in the world.” His boss soon found himself longing for Sununu’s take-no-prisoners style, which for a time at least got results. More recently, Andrew Card struggled to corral the big personalities and broad portfolios of George W. Bush’s cabinet. His inability to wrangle Colin Powell, Donald Rumsfeld, and especially Vice President Dick Cheney contributed to a rancorous atmosphere and catastrophic policy decisions like the invasion of Iraq. When Rumsfeld himself was chief of staff to President Ford, he had no problem standing up to administration heavies. He told Secretary of State Henry Kissinger that if he couldn’t show up on time to meetings in the Oval Office, he should stop coming altogether. And when the president wanted to go to Tip O’Neill’s birthday party, Rummy told him he’d have to walk.

The sergeant or the milquetoast; vulnerable to backstabbers or enemy fire: it is a delicate balance to strike. That is especially the case if you are Reince Priebus trying to manage a mercurial chief executive and an unconventional West Wing staff. Priebus might consider reading this book.

The White House chief of staff is a modern position, dating from the 1950s. Sherman Adams was the first official chief, under President Eisenhower, but the job caught on only during the Nixon administration, after Presidents Kennedy and Johnson ran their own shops. Yet elements of the position have existed in other forms, and one of the weaknesses of The Gatekeepers is that it disregards the job’s fascinating antecedents. Woodrow Wilson had his Colonel House and Franklin Roosevelt his Harry Hopkins: advisers who were close to the president personally, enjoyed his confidence, and advised him on matters of policy and politics. Other presidents used private secretaries and personal assistants for the same purpose. Adams gets barely two pages in this book, even though he was a fascinating figure who perhaps first embodied our hard-bitten image of a chief. Time magazine described him as a grizzly bear with a barked shin.

H. R. Haldeman created the template for the modern chief of staff under President Nixon, devising the West Wing staffing system that most subsequent administrations have followed. There was a chain of command leading up to the chief, whose role was to control access to the president and tee up issues for his attention. Haldeman told his team that the president’s most valuable asset was his time, and he refused to waste a minute of it on issues that were not properly vetted or that could be resolved by others. What he wanted in a staffer was someone who “would remain in the background, issue no orders, make no decisions, emit no public statements,” and who was “possessed of a high competence, great physical vigor, and a passion for anonymity.” Haldeman lived out that credo, sitting against the wall during cabinet meetings, and handling every detail of Nixon’s presidency.

What he lacked was the ability to keep his principal from his own worst excesses. At times he tried. Whipple recounts a scene in which Nixon ordered Haldeman to give lie detector tests to every employee of the State Department. Haldeman responded with passive resistance, declining to institute a program that would have been dubious legally and impossible practically, and explaining away his slow-footedness until Nixon lost interest. Yet Haldeman also enabled Nixon’s paranoia and vindictiveness. He matched the president’s anti-Semitism slur for slur. White House recordings show that when Nixon finally let Haldeman go, it was a mawkish scene in which the inebriated president clearly knew he was making a loyal soldier fall on his sword. “Let me say you’re a strong man, goddamn it, and I love you…By God, keep the faith. Keep the faith. You’re going to win this son of a bitch.”

Here we reach the matter of timing, knowing when to leave the stage: what Jerry Seinfeld described as “showmanship.” Rumsfeld advises new chiefs of staff that they have to be willing to be fired, which is another way of saying they mustn’t be afraid to tell the president what he doesn’t want to hear. But the most successful chiefs leave the job of their own accord. Leon Panetta told President Clinton that he would serve for a maximum of two years; Baker made it clear that he would leave when the right cabinet position opened up. Rahm Emanuel—who tempered outrageous brashness with an extraordinary ability to move legislation—left the Obama administration after a year and a half to run for mayor of Chicago. By contrast, Sununu and Regan resisted the door. Sununu ignored multiple messengers whom President Bush sent to fire him. Regan left the Reagan administration in a fit of pique, submitting a one-line letter of resignation after he had been replaced and then never speaking to the president again.

What makes a successful chief of staff? The Gatekeepers both does and does not supply the answer. The book is an overview rather than an in-depth study, with some chiefs earning only a page or two of superficial analysis. And Whipple relies on too many blockbuster interviews of cabinet secretaries and even a president (Bush 41), overlooking White House staffers. Yet Whipple has done readers a service by presenting all of the chiefs of staff here, in one place, for side-by-side comparison. Reading about them sequentially, one divines four essential competencies. A chief of staff must have mastery of management, policy, and politics—and he must have the president’s confidence. Very few have combined all four.

Two of the best chiefs worked for Bill Clinton: Leon Panetta and John Podesta. The first two years of the Clinton presidency were aimless ones, with the famously disorganized president setting a tone of scattered ineffectiveness. Arriving in 1994, Panetta changed that, with the help of ace deputy Erskine Bowles, who would take over after Panetta left in 1996. They added structure to Clinton’s schedule, closed his perennially open door, and relentlessly focused on his strategic priorities. Panetta had “an iron fist in a velvet glove,” cultivating friends with his jovial manner but, like Baker, cracking down as needed. He made an ally of Hillary Clinton, and steered the West Wing through the government shutdown. John Podesta was Clinton’s final chief, and later proved an invaluable adviser to President Obama. Podesta helped the administration regain direction and purpose after the Monica Lewinsky scandal and subsequent impeachment. A brisk policy expert with fine political antennae, Podesta was well liked by his staff, who continue to remember him fondly.

Lower down the list are Denis McDonough, President Obama’s final chief of staff, Josh Bolton under George W. Bush, and Dick Cheney, who served President Ford. McDonough was simpatico with his president in a way of few other chiefs, an alter ego to the solitary and analytical Obama. With Podesta’s help, McDonough made effective use of executive orders late in what was shaping up to be a disappointing second term, although he was unable to accomplish as much as the hyperactive Emanuel. Bolton reimposed structure in President Bush’s White House by reasserting control over the staff and the cabinet. And under Ford, Cheney was an effective chief mainly in contrast to his predecessor Rumsfeld, who had driven everyone crazy with his bottomless arrogance and general unpleasantness. In a bit of irony for modern readers, the master of darkness was known in his youth as a laid-back people person, with “a softer management style” than Rumsfeld. Under Cheney, “the place really hummed.” But then, the Ford presidency did not end particularly well.

By common consent, the most effective White House chief of staff ever to hold the position was Jim Baker, who read the riot act to poor David Stockman in 1981. Nearly every subsequent chief has sought to emulate him. Baker had an uncanny command of policy and politics, managed the West Wing efficiently, and enjoyed Reagan’s full confidence. He was prepared for each meeting and spoke with the authority of the president. “Day in and day out, he’s focused,” said Margaret Tutwiler, former undersecretary for public diplomacy and public affairs at the State Department under George W. Bush. “He does not wing it. He thinks before he speaks.” Baker was well matched to his boss, for his knowledge of detail complemented Reagan’s lack of it. As campaign manager Stuart Spencer put it, “Reagan was, ‘I’ve got a role to play, I’ve got a script to learn—and you’re a producer, you’re a director, and you’re a cameraman: Now you do your job and I’m gonna do mine.’” The upshot, Spencer said, was: “You’ve got to have one hell of a chief of staff!”

Baker was. One of Whipple’s interviewees described him as a maestro. He forged quick alliances with Nancy Reagan and her close friend Mike Deaver, collected members of the press, and hand-picked staff in every department. He was a straight shooter and tough, but no tyrant, and with his sharp Texas charm he won the staff’s loyalty. A pragmatist, Baker focused on legislation that was achievable rather than ideologically pure. He reasserted command in the West Wing after the assassination attempt on Reagan in 1981, and used the president’s ensuing swell in popularity to advance budget legislation. Baker’s hardest test was managing the conservative side of Reagan’s cabinet, particularly Edwin Meese and Jeanne Kirkpatrick. Yet he won more battles than he lost, and was asked to return by the first President Bush. Tom Wilkinson memorably portrayed Baker in the Bush/Gore movie Recount, and gave a hint of his legendary effectiveness as he took control of a roomful of tentative staff. “Now, we can sit here drinking tea and discussing the virtues of federalism, or we can start throwing punches.”

The Carter administration, by contrast, offers a cautionary tale. Disregarding Haldeman’s staff structure, Carter initially declined to hire a chief of staff, instead attempting to recreate the “spokes of the wheel” plan of Kennedy’s West Wing. The president sat at the center, and each of his senior advisers shared equal access. A model intended to bring the president a diversity of viewpoints resulted in chaos, with murky lines of sight and few objectives achieved. As Carter speechwriter James Fallows later wrote in a scathing critique:

Carter and those closest to him took office in profound ignorance of their jobs. They were ignorant of the possibilities and the most likely pitfalls. They fell prey to predictable dangers and squandered precious time. . . . Carter did not devour history for its lessons, surround himself with people who could do what he could not, or learn from others that fire was painful before he plunged his hand into the flame.

Several days before President Trump’s inauguration, the New York Times wrote that the incoming chief of staff, Reince Priebus, was inheriting “one of the most daunting and uncertain situations any recent chief of staff has faced.” The president’s most famous punchline is “You’re fired,” and during the transition he boasted, “We have no formal chain of command around here.” Priebus, in theory, has authority over Chief Strategist Steve Bannon, Counselor Kellyanne Conway, and Senior Adviser Jared Kushner. But Kushner is family, and Bannon emerged in January as Trump’s point man. Vice President Mike Pence has broad authority that may supersede everyone’s but Trump’s. News reports abound describing these individuals jockeying for the president’s favor. In his prior life at the Republican National Committee, Priebus was an institutionalist renowned for his fund-raising. Those skills got them to the West Wing, but they won’t help in a knife fight.

The Gatekeepers was written before President Trump took office, but it is impossible to read without an eye to current events. The book’s lesson is that a presidency’s success is bound up closely with the abilities and authority of his chief of staff. In his boldest claim, Whipple even asserts that the Iran-Contra affair would not have happened had James Baker still been Reagan’s chief. That is unknowable but carries the ring of truth; Whipple writes that “a plot to sell arms to Iran through shady middlemen with Swiss bank accounts would never have passed Baker’s smell test.” Perhaps that is a fifth competency: every chief of staff needs a strong nose. Let’s hope Reince Priebus has one.