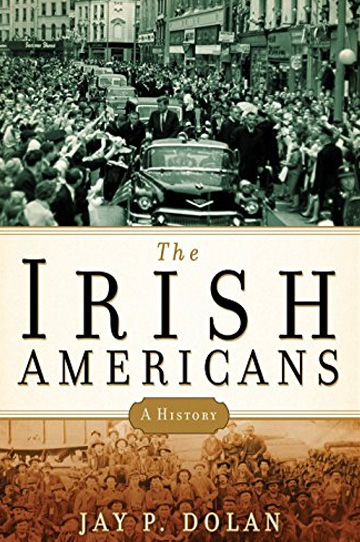

The Irish Americans: A History

November 26, 2008 | San Francisco Chronicle

An old Chicago joke has President Kennedy, Premier Khrushchev and Mayor Richard J. Daley as the only passengers on a sinking boat with one life jacket. Kennedy and Khrushchev each claim the jacket, the former as the leader of the free world, the latter as the head of the communist revolution. Daley, that Irish Catholic boss of the old school, persuades them to put it to a vote. Daley wins, eight to two.

Local machine politics in the 19th and 20th centuries were dominated by Irishmen who trended thuggish but knew how to get things done. James Michael Curley, the rascal king of Boston, ruled that city as mayor for a total of 16 years — including a few months from prison. The Richard Daleys, father and son, have as of this writing run Chicago for a combined 40 years; they have beautified the city and made it hum like a fine automobile that spits out filthy exhaust. And as for William M. Tweed, when millions of hated Irish arrived in the 1860s and New Yorkers saw “St. Patrick’s vermin,” Boss Tweed saw votes, and bought them with any currency at hand. He built up an alliance between the Irish and the Democratic Party that until recently was as durable as any in American politics.

Irish Americans’ provincialism ended the day John Kennedy was elected president. It’s no exaggeration to say that Kennedy’s ascendance was as monumental to Irish Catholics as Barack Obama’s recent election has been to African Americans. Historian Jay Dolan explains why in “The Irish Americans,” arguing that perhaps no ethnic group in this country except for African-Americans has been more historically despised. Many Irish came to America during the colonial era as indentured servants, destined to be auctioned off “like cattle in a market” if they survived the trans-Atlantic journey. Having escaped anti-Catholic penal laws in Ireland, they faced new ones in America; Maryland, for instance, denied them “the right to vote, worship publicly, hold office, practice law, and establish Catholic schools.” During the 19th century as competition for jobs enhanced the stakes of ethnic rivalry, nativists warmed their hands on the flames of anti-Irish riots.

But today Irish Americans are as prosperous and well educated as nearly any ethnic group. The story of their ultimate arrival after years of “No Irish need apply” signs — and their ability to maintain solidarity generations after assimilating into American culture — is best told as a series of journeys, high-profile “Nixon in China” moments that cultivated a sense of purpose and stoked the nationalist fire. Charles Stewart Parnell, the father of Irish Home Rule and land reform, energized a generation of Irish Americans during an 1880 visit in which he decried the English landlord system. Eamon de Valera, Ireland’s political leader for much of the 20th century, had a similar effect when he visited in 1919 to rally support for Irish independence. And of course Kennedy and Bill Clinton both famously traveled across the Atlantic, the former in a sort of extravagant birthright pilgrimage from Hyannis Port to Dublin, the latter to Belfast in a popular and ultimately successful push to end to the Northern Ireland troubles.

Dolan’s book is scholarly and earnest, and will probably become the standard reference on the history of Irish America. Rather than breaking new ground, Dolan assembles and organizes sketches of prominent figures, compiles demographic information and spots broad trends, such as Irish leadership in the labor movement (Mother Jones was born in County Cork). “The Irish Americans” is also a work of capital-H history in the sense that nothing recent qualifies. Dolan touches upon but leaves open contemporary issues like Ireland’s transformation from one of Europe’s poorest countries to one of its richest, and the attendant implications for Irish migration. For the first time in centuries, the spigot has reversed its flow; more people now immigrate to Ireland than emigrate from it. Perhaps one day expatriate Americans will cheer as Ireland elects its first ethnically American president with as Yankee-sounding a name as John Fitzgerald Kennedy sounds Irish.