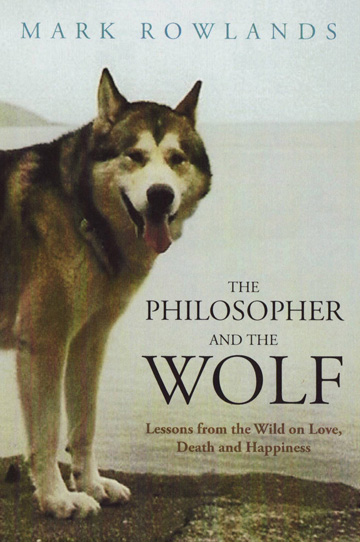

The Philosopher and the Wolf

April 21, 2009 | The Barnes & Noble Review

What distinguishes friendship between two people from friendship between a human and an animal? There are the drinking games, of course. And human friends also offer each other more complex reciprocal qualities (humor, shared experience, perspective) than humans and animals do (patience, dependability, loyalty). But more than that, admiration seems to be a subtly important difference. We unabashedly admire the physical qualities of our animal friends — the horse’s quiet majesty, the sprinting dog’s limitless capacity, the kitten’s cuddliness. By contrast, while we admire beautiful people, we tend to befriend those whom we esteem for other reasons, like talent or wit; if we’re too dazzled by their looks, we’re probably in love.

You’ll find no better description of a man’s admiration for an animal than this one, from Mark Rowlands’s extraordinary and wise book, The Philosopher and the Wolf, in which the author recounts the eleven years he lived in the company of a pet wolf named Brenin:

On our runs together, I realized something both humbling and profound: I was in the presence of a creature that was, in most important respects, unquestionably, demonstrably, irredeemably and categorically superior to me. This was a watershed moment in my life. I can’t ever remember feeling this way in the presence of a human being. That’s not me at all. But now I realized that I wanted to be less like me and more like Brenin. My realization was fundamentally an aesthetic one. When we were running, Brenin would glide across the ground with an elegance and economy of movement I have never seen in a dog. From a distance it looked as if he was floating an inch or two above the ground.

Rowlands’s unusual book — part autobiography, part philosophical discourse; harshly cynical yet somehow also inspirational — is above all a meditation on the nature of friendship, and on the human/animal bond, which is a remarkable but precarious and overlooked thing. This is not the sole province of the philosopher (Rowlands’s profession); but philosophers, from Jeremy Bentham to Peter Singer to Tom Regan, have a long and uncommon history of treating animals as a subject worthy of serious intellectual consideration. Rowlands’s own method is to intersperse autobiographical chapters with philosophical explorations of subjects like happiness, grief, and time, especially insofar as his life with Brenin helped him find answers. The book has much to teach us about our relationship to animals, and even more to teach us about ourselves.

The story begins when Rowlands buys Brenin as a wolf cub in Alabama, for $500. Coming from a family of intrepid big dog owners, Rowlands had casually gone to investigate a newspaper ad and ended up running off to the ATM to empty his bank account. He and Brenin lived in lockstep from then on. Rowlands was a drifter of a young academic, living now in Ireland, now in France — a misanthropic loner who found himself increasingly preferring Brenin’s company to that of other people. Brenin, a giant of 150 pounds, standing 35 inches at the shoulder on paws the size of baseball mitts, accompanied Rowlands everywhere, even napping under a desk as Rowlands delivered his philosophy lectures to rooms full of nervous students whose unzipped bookbags were occasionally invaded by a wandering nose in search of snacks.

For some, the first question to ask about this uncommon arrangement concerns the ethics and wisdom of taking a wild animal as a pet. Rowlands deals with this issue brusquely, arguing that we demean a wolf’s adaptability, its “intelligence and resourcefulness,” by adopting a restrictive and simplistic view of its proper place in the natural world. His argument is persuasive, although it stretches a bit when one considers the improvident readers who will follow his example rather than his warnings and buy pet wolves. Still, this line of questioning rather misses the point, like complaining that the boys in Dead Poets Society ought to have been studying for finals instead of reading Whitman. Rowlands gave Brenin a very good life, providing him much more attention and consideration than most people give their pets. There is something deeply moving about a man referring to an animal, plainly and unsentimentally, as his best friend. Toward the end of the book, as Rowlands whispers his last words to Brenin — “We’ll meet again in dreams” — the reader, through tears, contemplates not the appropriateness of this extraordinary friendship but the blessing of it.

Rowlands’s admiration for Brenin eventually transcends the aesthetic to encompass the metaphysical. “We stand in the shadow of the wolf,” Rowlands writes, “not the shadow cast by the wolf itself, but the shadows we cast from the light of the wolf.” He contrasts the deceptive, scheming nature of simian intelligence with the guilelessness of the lupine. Like all predators, wolves of course exploit weakness, but humans go a step further and manufacture it, as in animal experimentation (a topic on which Rowlands briefly but ferociously expounds). These highly evolved abilities, we tend to think, set us above other animals, but Rowlands thinks they merely set us apart from them, for “superiority in one respect is likely to show up as a deficiency elsewhere.” The same holds true for our ceaseless pursuit of happiness. Brenin, by contrast, was limited, or perhaps freed, to live each moment as it happened, full of wonder and delight, without constantly focusing on the way he was feeling.

Not everyone has the capacity or indeed the inclination to befriend an animal as intimately as Rowlands has done. Animals cannot play Scrabble or pay compliments; they don’t have exciting news and won’t discuss yesterday’s game. What they do offer, to those who open themselves to it, is a powerful constancy, an uncomplicated friendship that simplifies and heals as it reminds us of our ancestral life before we struck the fraught bargain of great resourcefulness and ingenuity in return for a greater capacity for malevolence and deceit. It is a rare writer indeed who is able not only to capture and celebrate this communion, but also to live it, forcefully. Reading this book, like living in kinship with an animal, offers a chance for something very fine to rub off on us — like brushing against a monarch’s cape and being sprinkled with gold powder. The name Brenin, after all, is Welsh for “king.”