A Champion Who Couldn’t Win

August 30, 2014 | The Wall Street Journal

SHOULD AN ATHLETE become an activist? Does a black athlete have a choice? In 1966, Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted by the Army for service in Vietnam; he fought the case successfully all the way to the Supreme Court. Mr. Ali’s contemporary Bill Russell was famously antagonistic toward basketball fans in race-troubled Boston and declined to attend a ceremony retiring his Celtics jersey in 1972. Many pioneering black athletes from the preceding generation preferred to let their achieve· ments do the talking. In this way Jackie Robinson helped to integrate baseball in 1947, and Althea Gibson in the 1950s broke the color line in tennis. Whatever their philosophy of race politics, it is safe to say that each of these competitors offended someone.

No modern athlete approached civic responsibility with greater thoughtfulness, eloquence or ambivalence than the tennis champion Arthur Ashe (1943–93), who won three majors on his way to becoming the No. 1 player in the world. “I guess I’m a militant,” he said revealingly in 1968, even as he rejected the demands of the Black Power movement. In those years, “the moderate progressive’s hero could be the reactionary’s nigger and the revolutionary’s Uncle Tom,” Ashe tartly remarked, summing up his uneasy role as a civil-rights moderate. Today he is remembered for embodying the ideal tennis gentleman with quiet dignity in the face of racism and illness (he died of complications from AIDS). The biggest matches of the U.S. Open, currently taking place in Queens, are played in Arthur Ashe Stadium. He is the patron saint of American tennis.

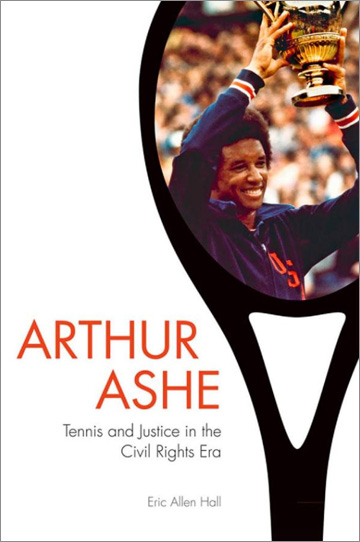

Eric Allen Hall’s “Arthur Ashe: Tennis and Justice in the Civil Rights Era” explores Ashe’s complex and fascinating public life while chronicling the reluctant integration of a country-club sport. A strong book on an outstanding topic, it serves as a reminder that Ashe’s tragic death has to some extent eclipsed his life’s work on behalf of racial equality. A fiercely private man, Ashe did not, at the end, want his illness to define him in the eyes of the public. But as Mr. Hall shows, he never let himself be defined by others. He chose his own battles and fought them on his own terms.

Ashe had to choose carefully, especially as a young man. A native of Richmond, Va.—today a statue of him stands near monuments to Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson—he learned to play tennis in the city’s segregated parks. At a tennis camp for promising African-American players, his coach taught him to retain his composure at all times, returning any ball that landed within two inches of a line and never arguing with an umpire. Ashe’s emotional control and “icy elegance” made him the perfect student. After he became the first black man to win Wimbledon, in 1975, he barely celebrated, merely pumping a fist and flashing a smile. But unlike, say, Larry Bird or Tiger Woods, Ashe did not make a fetish of his poker face. He succeeded in tennis by co-opting its gentlemanly ethos, but he was also a gentleman by nature.

Ashe ventured into politics gradually, and only when racism directly affected him. He did not travel to the South to participate in the Freedom Summer in 1964. He played tennis at UCLA, across town from Watts, and kept his head down while riots blazed in 1965. His first forays into civil rights were notably moderate affairs, such as an appearance on “Face the Nation” in 1968 just after he had won the U.S. Open, during which he called for better enforcement of the federal civil-rights laws.

His interest in civil rights had its limits. He would refuse to support the movement for women’s equality in tennis during the early 1970s, when women earned one-tenth the prize money of men. Deriding “girl” athletes and suggesting that men played a more exciting game, Ashe revealed a petty chauvinism. He also made a few enemies on the women’s tour, notably the outspoken Billie Jean King, who had no time for his moderate, incremental tactics. “Don’t tell me about Arthur Ashe,” she famously said. “Christ, I’m blacker than Arthur Ashe.”

But Ashe’s gradualism hardened into decisiveness when he found his issue: apartheid. South Africa, Mr. Hall suggests, was an unapologetically racist state that even a moderate like Ashe could safely criticize. “Antiapartheid protests would become his contribution to the black cause,” Mr. Hall writes. Ashe became an outspoken opponent of Prime Minister B.J. Vorster’s government, though he defended individual South African players and rejected demands from black radicals to forfeit matches against them. When Vorster denied Ashe’s visa application to compete in the 1969 South African Open, the tennis player launched a battle that would last two decades. He joined other activists in seeking U.S. sanctions against South Africa and demanded that the South African Open be removed from the official tennis circuit. “For once,” Mr. Hall writes, “Ashe refused to compromise.”

Ashe’s emphasis on South Africa alienated civil-rights leaders who thought he should focus on issues closer to home. Yet he continued applying for visas and finally received one in 1973. Ashe insisted on an integrated grandstand at the tournament, but the South African government honored its promise in at best a superficial way and did not make the change permanent. He also drew criticism during the trip by staying at the estate of a wealthy white man rather than in the slums of Soweto.

Throughout the trip, Ashe struggled to find the right balance between sports and politics. The best way for him to make a statement against apartheid, he felt, was by winning the South African Open. Doing so required rest and diligent practice. But he also wanted to tour Soweto and meet with antiapartheid leaders. In today’s era of the unified athlete—all single-minded purpose and training and protein blasting—one wonders whether it is still possible to compete at the highest levels while also working a political portfolio. The modern tennis champion is a monomaniac. Rafa Nadal’s left hand was made to hold a racket, not a banner.

Mr. Hall’s account suggests that, when it came to certain issues, Ashe was prepared to let his game suffer. Indeed, his sense of priorities in the face of world-shaking events was one of his most handsome qualities. In his memoir, “Days of Grace” (1993), he suggested that with his efforts to fight apartheid he was trying to make up for his inaction during the 1960s. After retiring, he began writing books and teaching a college course called “Education and the Black Athlete” at Florida Memorial College. He proudly said that his multi-volume history of African-Americans in sport, “A Hard Road to Glory” (1988), was “more important than any tennis titles.” And he continued to protest apartheid and the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela, even getting himself arrested during a protest at the South African Embassy in Washington in 1985.

Toward the end of his career, Ashe encountered a new generation of me-first tennis stars, including Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe, who threw rackets, cursed opponents and shouted at umpires. Ashe found their antics appalling and a rejection of the values he stood for as an athlete: composure, reserve and sportsmanship. In a sense, this, as much as any speech or march, sums up his complicated civil-rights legacy. Arthur Ashe understood that in the lily-white sport of tennis in the 1960s and ’70s, the classiest guy on the court had to be an African-American. He was exactly what tennis needed when it needed him. He could have done more, but he did enough.