Mr. Bellow’s Planet

April 10, 2015 | The Wall Street Journal

IN THE WINTER of 1949, Saul Bellow needed an epiphany. Living in Paris and bogged down writing a dour novel about a man dying in a hospital room, he felt hemmed in on all sides: “deafened by the noise of life, by cries and claims and counterclaims and fantasy and desire and ambition for perfection, by false hope and error and fear of death.” Friendless, blue and uninspired, he placed a fresh sheet in the typewriter and decided to try something different. He began to write the novelistic autobiography of a childhood friend named Augie, who was full of beans and would yell while playing checkers, “I got a scheme!”

Out came prose like a wild locomotive with no brakeman. The track would bear this hurtling train for 600 astonishing pages, which overflowed with dazzling metaphors and boundless virtuosity. Conventional language yielded to outrageous characters. There was Grandma Lausch, “an autocrat, hard-shelled and jesuitical, a pouncy old hawk of a Bolshevik.” There was Five Properties (don’t ask), who emerged “windburned and hearty-blooded, teeth, gums, and cheeks involved in a bursting grin.” And there was a bald eagle named Caligula who would land on your arm “with that almost inaudible whiff of his spread wings that’s so fearful in itself.” When he took flight, “it was glorious how he would mount away high and seem to sit up there . . . beating his way up to the highest air to which flesh and bone could rise.”

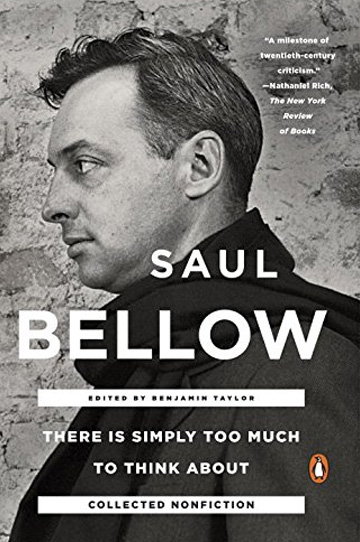

This was “The Adventures of Augie March,” Bellow’s first masterpiece. Its publication in 1953 heralded the arrival of one of the 20th century’s great artists. This year is the centenary of Bellow’s birth and the 10th anniversary of his death, and it looks to be a year of riches. Two major works are planned. In May, the first volume of Zachary Leader’s highly anticipated biography will appear. And just published is a new collection of Bellow’s essays and assorted nonfiction, “There Is Simply Too Much to Think About.” It sits handsomely next to Bellow’s collected letters from 2010. Both the letters and the essays have been edited by Benjamin Taylor, who deserves our gratitude for assembling two extraordinary collections.

Bellow’s discovery of Augie March in Paris is one of the highlights of “There Is Simply Too Much to Think About.” Also included are critical and narrative essays, book and film reviews, travel writing, interviews, speeches (including the 1976 Nobel lecture), and occasional works. In Mr. Taylor’s fine presentation, the book sets out to answer a ponderable question. In Bellow’s words: “Undeniably the human being is not what he commonly thought a generation ago. The question nevertheless remains. He is something. What is he?”

To the extent there is an answer, it is better reproduced than summarized. These pages contain scores of Bellow’s inimitable lines of wise and humane portraiture. This is a publisher who gave Bellow some work in the mid-40s: “Solid, British, sanguine, smoking pipes, wearing boots not shoes, tweeds not flannels, well satisfied with you, with himself, with the rich fittings of his office, he was a relaxed executive.” This is President Carter’s national security adviser: “Mr. Brzezinski has a pleasing face, a narrow aristocratic Polish nose in which I, raised among Poles in Chicago, can identify a characteristic irregularity of line, the Slavic eye frame and a whiteness of the skin more intense than that of Western Europe—not a pallor but a positive whiteness.” And this is your everyday hippie: “Meeting an old Village intellectual, now gray-bearded and hugely goggled, I find him as densely covered with protest buttons as a fish is with scales.”

Such phrases are miracles of prose, and their appearance is a cause for celebration. But “There Is Simply Too Much to Think About” is notable for writing of another sort. In these essays Bellow grapples with ideas more often than characters. He stretches out and explores questions about the past and future of literature, the moral and aesthetic dimensions of art, the problem of experience, and the temptation of politics. The writing is more earnest and less animated than in Bellow’s fiction—understandably, for developing an argument is a snore next to telling a story. Some of the essays in this volume go on a little too long as Bellow explores the nature of the self or challenges the English professors—he despaired of English professors—on their own clunky terms.

This type of discourse nevertheless has a foundation in Bellow’s literature. A favorite device in his novels was to let a scoundrel drop a reference to Tocqueville or Marx, revealing an unexpected sheen of intellect and a touching hint of self-improvement. Bellow returned again and again to the juxtaposition of the highbrow and the lowbrow: the bookies and jazz musicians who dabbled in philosophy. But the low was his natural register; it was the boat’s hull and the ideas were just the trim. Many of these essays seem like Bellow’s slightly overeager attempt to establish his intellectual bona fides, to prove that there was depth to his characters’ clever musings. Yet after pages of abstraction, he writes off abstraction itself as fussiness. To the chip on his own shoulder he replies: “I believe simply in feeling. In vividness.”

Bellow learned to pair the high with the low on the streets of Chicago in the 1920s. It was the city of Al Capone and Big Bill Thompson; there were “gangland killings almost daily.” His father worked in lumber and coal, and young Saul helped make fuel deliveries to the Jewish bakeries throughout the city. As a result, Bellow explains in an interview from 1999, he knew the railroad districts, saw the fights and the guns, and observed the union bosses and crooked politicians. Coal paid his way through college at the University of Chicago and then at Northwestern. With campuses at the southern and northern tips of the city, these academic redoubts ensured that he would learn the whole damn place.

To Bellow, Chicago was a “center of brutal materialism” and a place of constant reinvention. Old buildings came down, and new ones went up. Trains passed through in a steady and reassuring dynamism. He writes that a Chicagoan who “wanders about the city feels like a man who has lost many teeth. His tongue explores the gaps.” Chicago rose like an oasis in a sea of corn; it was Midwestern and friendly but had earned itself a strut. What would Bellow make, one wonders, of the gleaming Millennium Park that has replaced the wasteland between Michigan Avenue and the lake, or the new home of the White Sox? On the other hand, as much as things change in Chicago, they also stay the same. Four of the past nine governors of Illinois have served time in prison, and the city’s current mayor is a thug.

The other American metropolis in Bellow’s life was New York. He never loved it. “I always felt challenge and injury around the corner,” he writes. “I had always considered it a very risky place, where one was easily lost.” His diatribe against New York City as “the center of the culture business” rather than the country’s true literary capital will annoy Manhattan grandees, but it rings true to those of us west of the Hudson. “There is only the idea of a cultural life” in New York, he argues. “There are manipulations, rackets and power struggles; there is infighting; there are reputations, inflated and deflated. Bluster, vehemence, swagger, fashion, image-making, brain-fixing—these are what the center has to offer.”

On display throughout “There Is Simply Too Much to Think About” is Bellow’s aggressive independence of spirit. He did not like others trying to pin him down; art, he felt, needs to breathe. A secular Jew who embraced his faith late in life, he could be prickly about the expectations that were placed on him: “Is he too Jewish? Is he Jewish enough? Is he good or bad for the Jews?” he rhetorically asks. He took issue with those “who feel that the business of a Jewish writer in America is to write public relations releases, to publicize everything that is nice in the Jewish community and to suppress the rest.” Bellow believed that his religious heritage and his politics were his and no one else’s. They existed to serve his art, as extra dabs of paint on a palette. He resented intrusions that could only muddy their brilliance.

The loveliest work in this collection is called “Ralph Ellison in Tivoli,” from 1998. In it Bellow describes living with Ellison, a writer he admired, in a large, dilapidated house in upstate New York between marriages. It has all the elements of a fine short story, including setting, tension (Ellison’s dog would relieve himself in Bellow’s herb garden) and, above all, a beloved character to profile. “He came down to get his breakfast in a striped heavy Moroccan garment,” Bellow writes of Ellison. “He wore slippers with a large Oriental curve at the toe. He was a very handsome man.” Years later Bellow retired to the pastoral beauty of Vermont. After breakfast he would carry his coffee and his memories out onto the porch. Looking over the fields, he observed that the “dew takes up every particle of light.” And Bellow, bless him, breathed life into every word.