Ink-Stained Life

May 20, 2025 | The Wall Street Journal

Before he became a spy or a novelist, Ian Fleming was a newspaperman. In 1933 he reported for Reuters on a blockbuster show trial in the Soviet Union in which a group of British engineers faced trumped-up charges of espionage. Fleming sat rapt in court, following the high drama of confessions, retractions and terrified prisoners. He also ensured that he would be the first to break news of the inevitable guilty verdicts by ripping out the phone cords in the courthouse press room. Yet a rival still scooped Reuters by screwing down the window where Fleming had arranged to have his copy dropped to a waiting car. His editor fumed by telegram: “Central news beat you with verdict by twenty minutes stop request explanation immediately.”

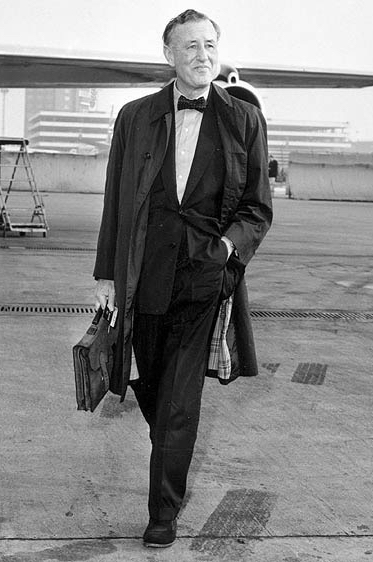

This episode, which appears in Nicholas Shakespeare’s outstanding 2023 biography of the creator of James Bond, reveals the totalitarian setting from which Fleming (1908-64) drew inspiration for his famous villains. Now comes Talk of the Devil, a collection of Fleming’s journalism and occasional writing. The volume briefly covers his World War II years in naval intelligence before moving on to his service as the foreign manager of the Sunday Times and later life as a novelist. This diverting collection shows Fleming’s strengths as well as his weaknesses. If shortened by a third to remove some of the entries about golf and cards, it would be even better.

A reporter at heart, Fleming is at his best when he has a chance at a snappy opener: “Some people are frightened by silence and some by noise,” he wrote in a piece looking back on the Dieppe Raid of 1942, which he observed at the time from the deck of HMS Fernie. He clinically itemizes the cacophony and brings the reader into the battle—an amphibious attack on the French coastline that went badly for the Allied forces—from the “whip-lash crack” of the 4-inch guns to the whine of the dive bombers. But the most enduring sound is “the deliberate, wooden, knock, knock, knock” of the German antitank guns cutting through the fray “with a disturbing authority.” It is “the sort of noise one hoped we were making, rather than the enemy.”

Talk of the Devil gives enviable glimpses into Fleming’s writerly productivity—he reports getting through 2,000 words a day on his first Bond novel Casino Royale, in three-hour morning sessions—and into the craft of thriller writing. “It is always a bad idea for the hero to fall in love with the villain’s daughter,” he advises. But the best prose here touches on subjects familiar to Bond fans: tropics and revving engines. Fleming’s beloved Jamaica was a retreat from which he could “watch the fireflies and listen to the distant surf on the reef”; the Seychelles emerged from the doldrums at sea with “the roar of our anchor chain echoing back to us from the emerald flanks of Mahé.” Singing the praises of his high-powered sports car, Fleming rhapsodizes, “the reason why I particularly like the Thunderbird, apart from the beauty of its line and the drama of its snarling mouth and the giant, flaring nostril of its air-intake, is that everything works.”

Fleming seemed to know his limitations as an essayist and armored himself by appearing mildly uninterested in his subjects. Many of his pieces here project a tone of droll boredom, as if by declining to try harder he might prove that he hadn’t failed to write something better. (“Security, except when it becomes counter-espionage, is a dreary subject and I have never envied the security men I have met in my life.”) It is worth nothing that there was unusually stiff competition in the category of midcentury British novelists who produced journalism on the side. Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell and Kingsley Amis all turned out brilliant hackwork and book reviews. George Orwell wrote the indelible essay “Shooting an Elephant” three years after Fleming covered Moscow. For all Fleming’s worldly charm, he is not in the same class as these peers.

Even with respect to fiction, Fleming occasionally acknowledges giving his best and coming up short. Reflecting on the moment that he completed Casino Royale, Fleming writes that he looked at the manuscript and felt ashamed: “The heroine is the purest cardboard. The villains out of pantomime.” Bond made Fleming rich and famous, and there is absolutely a talent in producing pulp that sells millions of copies: If there weren’t, more people would do it. Still, the reader senses from Talk of the Devil that while he had all the trappings of a satisfying writing life, the one thing Fleming lacked was literary respectability.

His background in wartime intelligence did give him the opportunity to weigh in on subjects of import, such as the work of Interpol. Yet some of Fleming’s articles on public affairs fail to reflect the sheen of that experience. Were he prime minister, Fleming writes, he would insist that all British firms devote 5% of their business to producing top-flight luxury goods regardless of cost: a silly idea. In an article about the FBI, Fleming praises J. Edgar Hoover’s “absence of greed for political power” and writes that, to the director, “a raw file, containing unconfirmed suspicions that inevitably implicated others . . . was a weapon which should never be used against an individual except to build up a case that would subsequently stand in law.” Whatever you think of Hoover, these fantastically naive sentiments are hard to take seriously.

It is no surprise—and perhaps no great fault—that James Bond’s creator is at his best when describing explosions, island breezes and fast cars, or that he begins to wobble the further afield he goes. Simple pleasures. There is much to be said for them.