Anchored in Space, Voyaging in Time

September 22, 2023 | The Wall Street Journal

On his first night in rehabilitation after a massive stroke at age 68, the writer Jonathan Raban took on a project. “I had long promised myself to read Tony Judt’s Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945—a long book that covered my own lifetime and a good test of my working brain cells,” Raban writes in his memoir, Father and Son. Yet his interest went further than subject matter or mental aerobics. The two British expatriates and contemporaries had something in common. Judt had publicly chronicled his struggle with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, continuing to dictate his work until his death in 2010. Here was an example of intellect unmarred by self-pity or physical limitation. “He puts to shame my own disablement,” Raban writes of Judt, “and reminds me of just how lucky I am to live in writerly solitude on my own terms still.”

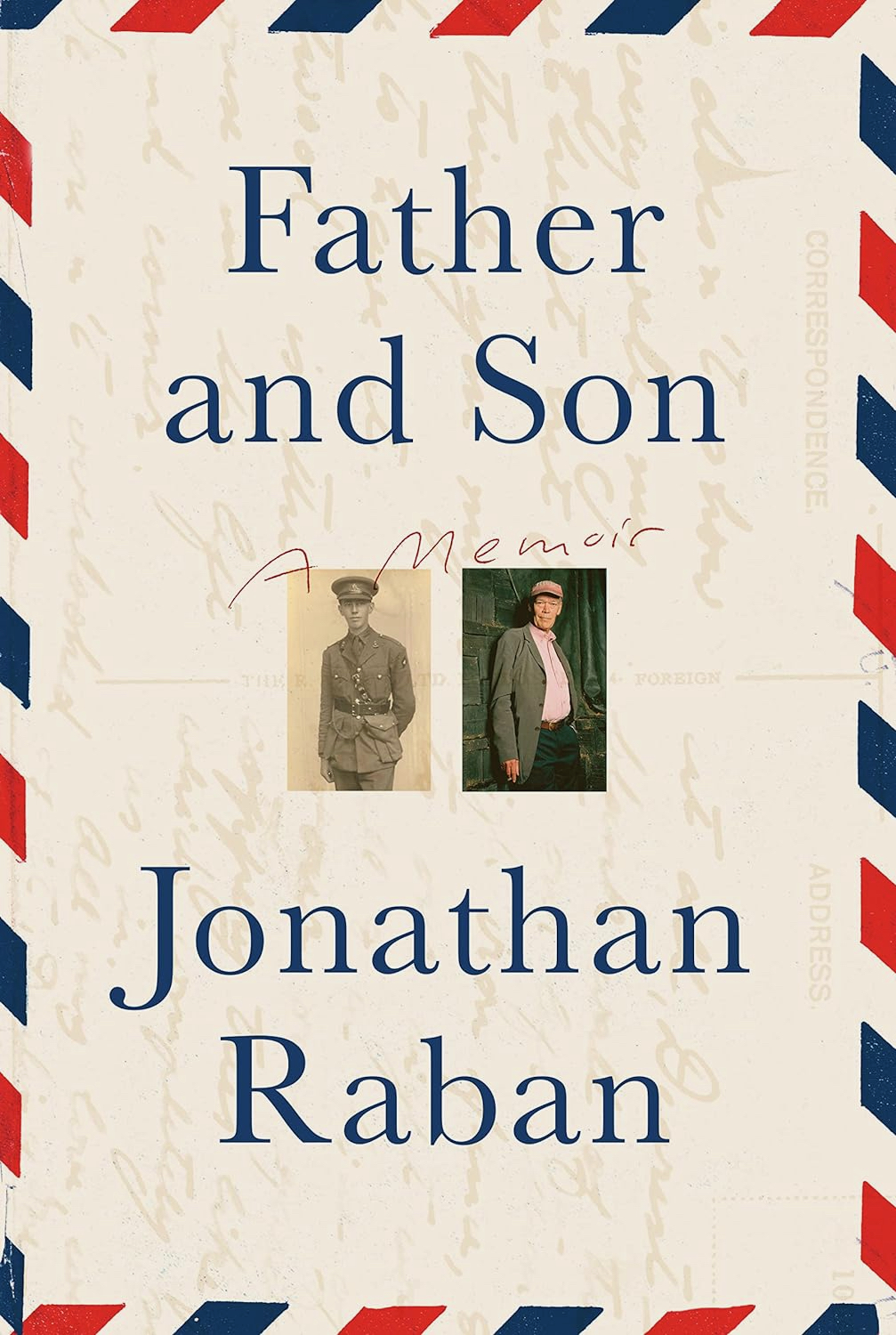

Raban’s memoir was likewise written using voice-dictation software and completed over the course of years. His editor, John Freeman, calls it “one of the most miraculous feats of writing I’ve ever witnessed.” Published posthumously following Raban’s death this past January from complications of his stroke, the book tells two stories in parallel. The first is Raban’s six-week stay in a Seattle rehabilitation center in 2011. The second is his father Peter Raban’s three-year separation from his wife and infant son while serving as a British army officer during World War II. As full of eloquence as it is free of sentimentality, the memoir is a parting gift from a figure of insight and fierce independence.

Given Raban’s prior renown as a travel writer, his stationary outlook in Father and Son is as cruel as an anchored ship. The author of some 18 books, including several novels, he worked in the tradition of Peter Matthiessen, V.S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux. These writers crossed back and forth between fiction and nonfiction and turned their journeys into literature. Raban’s Bad Land (1996), about Montana at the turn of the 20th century, won the National Book Critics Circle Award; several of his other travelogues explored American waterways by sailboat. Unsurprisingly, the best passages in Father and Son convey movement, as when the author recalls a trip through eastern Washington state: “I headed south on a road as true as a line of longitude.”

This interest in motion drives Peter’s story. It begins with Jonathan at his father’s bedside on the day before Peter died in 1996. The narrative then turns back more than half a century, to Peter’s evacuation at Dunkirk. There followed service in North Africa, then Italy, Palestine and Syria. While tracing this journey, the younger Raban paints a portrait of his father that is critically objective yet humane. The young artillery officer wore his class pretensions stiffly, as when he commented on the pleasant accommodations of his officers’ train. Unremarked by Peter: the enlisted men sleeping fitfully on straw in a cattle car. Raban also writes unsparingly of his father’s petty prejudices and bigotries. Yet Peter’s decency is evident as well: his coolness in action, willingness to sponsor his men for compassionate leave, and gentleness to his wife, Monica, as she anxiously awaited her husband’s safe return.

All of this is gleaned through correspondence. Peter and Monica exchanged letters that were passionate, ardent and frank about everything but combat. Their son experienced them as a revelation, so unlike the cheerless notes he received from his father while at boarding school. When writing to his wife, Peter played down the horror of war out of both duty (army censorship) and patronization (she’d fret!). Although he faced ample danger, particularly in the Anzio campaign, he rarely let on in his letters home. The younger Raban sets a warm—and exaggerated—tableau of the comforts of the pen during his father’s trench life: “Six feet below ground, working by the light of a storm lantern, the air of his snug burrow smelling of paraffin, freshly turned earth, and St. Bruno Flake pipe smoke, and with a bottle of NAAFI Scotch close to hand, Peter clearly took a writerly pleasure in inhabiting the world created by his own words—a world in which he could spend a blessed hour or two in exile from the war.”

Interspersed with Peter’s story are accounts of Jonathan Raban’s stroke and slow recovery. These chapters convey less motion, but the pages turn quickly because the lines are so raw. The rubble of Judt’s Postwar proves an apt metaphor for all that Raban must rebuild in rehabilitation. To say that he is not the ideal patient of the American healthcare system is like saying that a rusted chain dragged across broken glass might offend the ear. He is prickly, observant and blunt; he sneaks in wine and steals a chance to smoke. If there is one thing he cannot abide it is to be spoken to condescendingly, as when one nurse asks him to “go potty” or another tells him to wash his hands. Raban responds to these insulting remarks with salt and vinegar. “Do you know what the word ‘infantilization’ means?” he asks one nurse, who leaves his room with her nose in the air.

This is a vivid firsthand account of the indignities of rehabilitation: its institutional food, forced smiles, lack of privacy and petty humiliations, with each therapist looking “young, trim, impersonal, like a curator” of patients. Yet Raban would come to find the physical and occupational therapists to be his allies. Working one-on-one with them for extended sessions produces conversation and friendship, whereas revolving nurses regard “patients as an undifferentiated class.” This observation likely reflects Raban’s personality or his unique experience and is not at all fair to the nursing profession. Yet his portrayals of Richard, the urbane staff member who declares “Happy Bloomsday” in honor of James Joyce, or Kelli, the kind and encouraging physical therapist who agrees to read David Foster Wallace on Raban’s recommendation, undoubtedly reveal the best of Raban’s stay.

What links the two disparate narratives—the father dying near the beginning of the book and the son just after the end? Raban does not say, but his prose and the memoir’s structure offer a clue. As he tries to quantify the cognitive effects of his stroke, he writes, “I’ve now spent more than eleven years asking myself two questions every writing day: What have I lost? and Am I fooling myself?” It occurs to the reader of this remarkable book that both queries apply to the death of a parent as much as to medical recovery. How to reckon with the magnitude of such a loss? Are those who have endured it deceiving themselves that life can go on as before? These questions are so haunting that they are not asked directly. Not even a writer as wise as Jonathan Raban had the answers.