Cold War Cadenza

October 8, 2016 | The Wall Street Journal

A year after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik and two years after it crushed a democratic uprising in Hungary, the Russian people surprisingly adopted a young American pianist named Van Cliburn. Twenty-three years old, he was as tall and thin as a stalk of corn, with all the guile of a newborn baby. His electrifying performance at the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow induced a collective nostalgic swoon—a reminder during dark Soviet days of Russia’s grand Romantic past. The nervous jury consulted Nikita Khrushchev himself before awarding Cliburn first prize. Soon afterward Cliburn and Khrushchev met and made good-natured small talk—the first of its kind between the Soviet Union and U.S. in some time. “Why are you so tall?” asked the premier. “Because I am from Texas,” Cliburn replied.

In “Moscow Nights,” Nigel Cliff recounts this remarkable chapter of the Cold War, calling it the most improbable year in all of classical music. If it is tempting to overstate the moment’s cultural and political significance, Cliburn in Russia nevertheless offers a fascinating perspective on a decade of nuclear tests, espionage schemes and efforts to close the missile gap. This story is to the Cold War what pingpong diplomacy was to President Nixon’s opening to China. It is both entertaining and illuminating, and Mr. Cliff tells it beautifully.

The episode depends on the unlikely person of Van Cliburn himself, whom Time Magazine described as equal parts Liberace, Vladimir Horowitz and Elvis Presley. It took a young man of singular talent and innocence to bridge the two countries’ differences and to symbolize distinct but equally important things to each. To the Soviets he demonstrated Russia’s cultural superiority—an American in love with the very Russian people who first discovered his genius and thereafter claimed him as their own. To the Americans, who welcomed Cliburn home in 1958 with a ticker-tape parade in Manhattan, he showed that if Russia could win the space race, the United States could capture the arts. It was a dizzying role reversal for two adversaries that fought for every advantage. Cliburn was christened the American Sputnik and for a time was as famous as his namesake.

He was a rare virtuoso. The son of an accomplished pianist, Cliburn learned Rachmaninoff’s complex Concerto No. 2 in an astonishing two weeks and made the even more fearsome Third Concerto the centerpiece of his concert repertoire. He was known to practice until his fingers bled, a lonely occupant of the Steinway Hall basement until the early hours of the morning. Yet he combined drive and high art with a folksy Texan manner that disarmed and attracted men and women the world over. “Honey, ah’ve come to study with y’all,” he called down the hallway in 1951 to Rosina Lhévinne, the premier piano instructor at the Julliard School. His most common expression was to say, with a shake of his head, “Boy, isn’t it wonderful?” He was, Mr. Cliff writes, “an innocent-sophisticated man-child,” and everybody loved him.

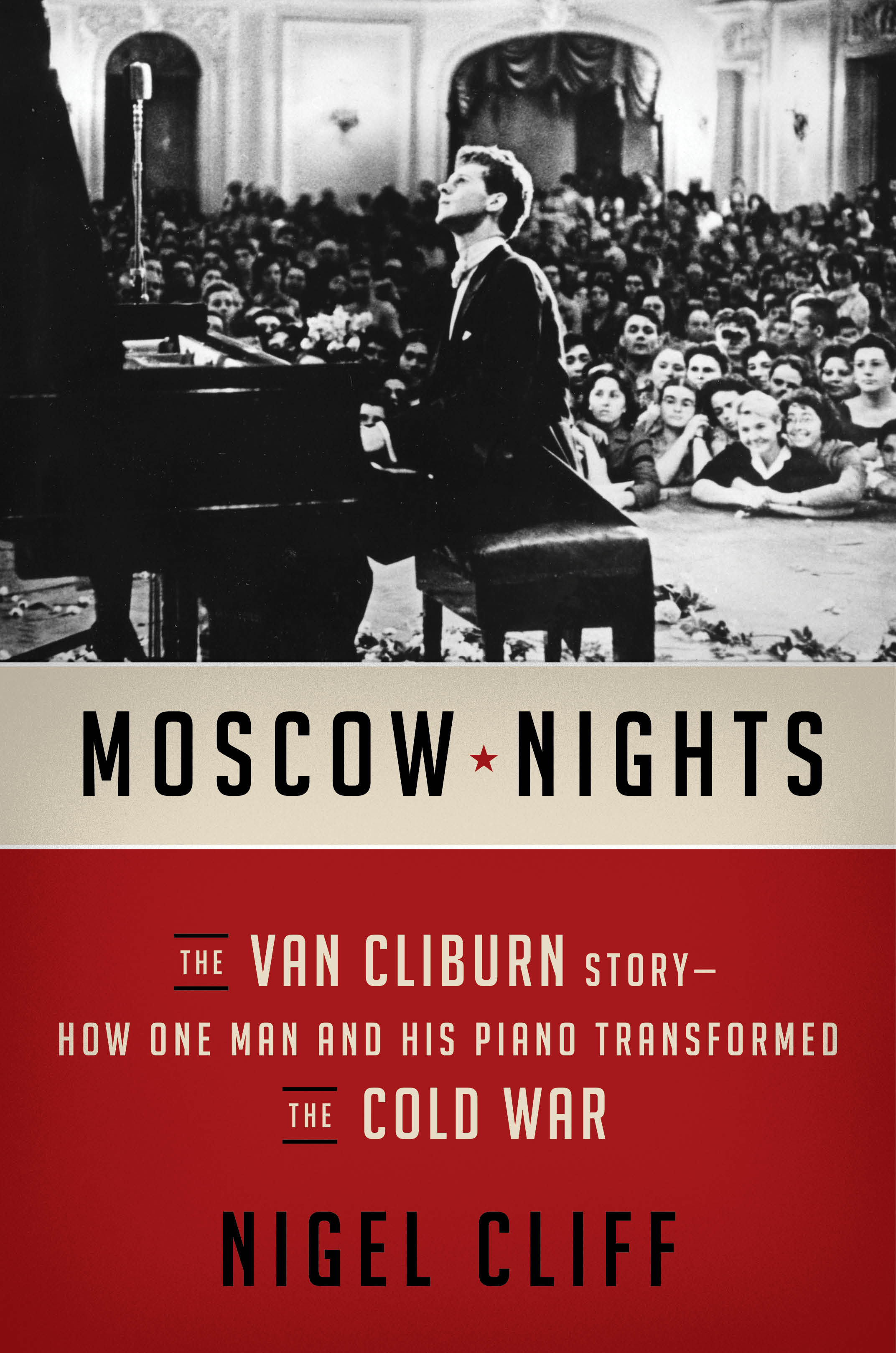

In an era when the great German composers Bach, Beethoven and Mozart dominated the musical scene, Cliburn’s tastes were hopelessly out of fashion. He was smitten with the ideal of the Romantic composer-virtuoso, admiring Liszt and Chopin and especially the Russians Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky. Near his piano he kept a portrait of Rachmaninoff—“a six-and-a-half-foot scowl,” in Stravinsky’s memorable description—as well as a picture of the Russian’s giant hands. Cliburn’s were large as well, and he deployed them for maximum schmaltz, drawing out tempos and exaggerating phrases to the point where, at times, artistry seemed to brush up against bad taste. His first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Concerto No. 1, all giant chords and dramatic pauses, is a full minute and a half longer than Martha Argerich’s. Onstage, he swayed and shook his head at the ceiling, radiating sublime agony.

Crowds ate it up. The Beatles never played the Soviet Union, but the Russians had Van Cliburn, who became a frequent visitor. Young women in particular adored him, throwing flowers, christening him “Vanya,” and shrieking over his good looks and wild curls. The feeling was mutual. “These are my people,” Cliburn said, proclaiming his “Russian heart.” He blew a thousand kisses and brought home countless gifts and trinkets. He would return to the country until the end of his life and in moments of high emotion embraced those around him and kissed them on both cheeks, in the Russian way.

Such gestures drew the notice of the FBI, which kept an eye on Cliburn to ensure that he had not fallen under the influence of Soviet authorities. At one point Lyndon Johnson considered booking him to play at a state dinner but first consulted J. Edgar Hoover. A memo from the FBI director summarizing their discussion shows Hoover advising Johnson “that Van Cliburn is a homosexual . . . . The President remarked that most musicians probably are homosexuals and I told him a great many are.” Johnson’s instinct was right: Cliburn was no threat to the U.S., and his sexual orientation was irrelevant. He played for every president from Harry Truman to Barack Obama before his death in 2013.

In the book’s most sobering pages, Mr. Cliff shows that the adulation Cliburn took from the International Tchaikovsky Competition was a lucky exception. The jury chairman was Dmitri Shostakovich, then perhaps the world’s greatest living composer; he had been cowed into a nervous wreck by Stalin’s persecution. Another top visiting performer in Moscow was the Chinese pianist Liu Shikun, who subsequently endured torture and imprisonment during China’s Cultural Revolution. When Mao abruptly released him after years of confinement, he ordered Mr. Liu to compose “more national-style music. And he should continue his performances.” Cliburn faced no such orders: He withdrew from public life in 1978, becoming one of classical music’s most famous recluses before returning to the White House for a triumphant performance for Mikhail and Raisa Gorbachev. With or without a piano, he would always be the Cold War’s golden boy.