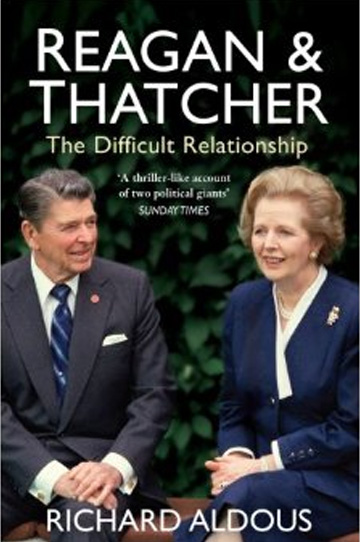

Isn’t She Wonderful?

March 21, 2012 | Salon, The Barnes & Noble Review

“Mr. President, the prime minister is on the phone.” So said the White House butler to Ronald Reagan on October 25, 1983, during a briefing on the United States’ impending invasion of Grenada. Margaret Thatcher was upset that Reagan had disregarded her advice against attacking the Caribbean nation (and Commonwealth member), where Marxist rebels had staged a coup. By invading, Reagan sought to check leftist advances and perceived Soviet influence in Latin America. He excused himself and took the call in the next room. In Reagan and Thatcher: The Difficult Relationship, Richard Aldous describes what happened next, based on interviews with the meeting’s attendees. They heard a series of “But Margaret”s on Reagan’s end, followed by long pauses in which Thatcher presumably hectored the president just as she hectored everyone else. Reagan returned to the briefing looking sheepish and said, “Mrs. Thatcher has strong reservations about this.” Yet the invasion went ahead as planned. In fact, he could not bring himself to tell her that it had already begun.

So went the special relationship during the 1980s, according to Aldous, a professor of British history and literature at Bard College. The great transatlantic right-wing love-fest was actually filled with spats, some of them venomous, and occasionally dishes were broken and pictures flung. Sometimes when Thatcher would call to bark at Reagan, he would hold up the phone for others to hear, saying, “Isn’t she wonderful?” He found her intellectually and personally fearless, and a useful ally when she agreed with him. When she disagreed, as she often did, he endured the browbeating but rarely changed course. He did not need to. As Thatcher knew all too well, Britain was a second-class power compared to the United States. She had to play Reagan and his divided staff skillfully in order to gain advantage for her country. Performing such delicate surgery was often too fine a task for her sledgehammer hands. In 2008 Thatcher was overheard to reminisce that “It all worked because he was more afraid of me than I was of him.”

Aldous’s splendid and sharp account of the Reagan-Thatcher relationship is agnostic on the merits of the policies that the two leaders pursued. It is also openly revisionist. The standard narrative that took hold in the final years of Reagan’s presidency was one of great personal fondness and ideological affinity. As the sun set on the 1980s, Reagan and Thatcher treated each other to lavish dinners and sentimental toasts in which mawkishness and superlatives were the order of the day. Broadly speaking, the picture of enthusiastic partnership that they presented was accurate. They had been through much together and saw eye to eye on major issues, such as privatization and the moral bankruptcy of Soviet communism. Yet Aldous contends that these surface pleasantries masked “a complex, even fractious alliance.”

Reagan and Thatcher is a welcome corrective to the standard thinking. Yet Aldous reveals the limits of his thesis by describing many occasions on which Thatcher and Reagan clashed fiercely in private, only to emerge in lockstep publicly. One such issue was the American military response to Libyan terrorism in 1986. Reagan sought Thatcher’s permission to launch jets from a Royal Air Force base for strikes against targets near Tripoli, and she initially resisted. But she came around soon enough and subsequently defended the action in strident terms to the British public. (François Mitterand, by contrast, denied permission for the jets to traverse France’s airspace.) Thatcher also voiced serious reservations about Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (the “Star Wars” program), which threatened to disrupt the West’s carefully calibrated policy of nuclear deterrence against the Soviet Union. Yet Britain was the first ally to sign up for SDI research, in 1985. In return for her loyalty, Thatcher won the president’s ear and his firm support when Britain’s interests aligned with those of the United States. Tony Blair was not the first prime minister to be derided as an American president’s poodle.

At times Thatcher was more like Reagan’s attack dog. Aldous recounts colorful scenes at G7 summits in which Thatcher took on Mitterand and Canada’s Pierre Trudeau when they tried to gang up on Reagan. She used her trademark mixture of brute force and coquettish sexuality: “Pierre, you’re being obnoxious. Stop acting like a naughty schoolboy!” (The late Christopher Hitchens swore that Thatcher once ordered him to “bow lower” in the House of Lords, and then spanked him on the backside.) Some of the closeness that developed between Thatcher and Reagan seems to have arisen from protectiveness toward each other during key moments of trial. She stuck by him during the Iran-contra affair, while he dropped everything and called her after the IRA tried to assassinate her with a bomb in 1984.

Personal relationships undoubtedly matter in statecraft, but in the end countries act primarily according to their interests. Hard realism caused the biggest strain on the alliance during the Reagan-Thatcher years: the Falklands War of 1982 between Britain and Argentina. The United States, which valued its Cold War alliance with Argentina, pushed hard for a peaceful resolution to the conflict, hamstringing Thatcher and infuriating her as she ordered warships into the South Atlantic. Yet when Argentina rejected a proposed settlement, the Americans stopped playing go-between and took Britain’s side openly and without reservation. And interests can sometimes be relaxed for friends, as when Reagan directed the Justice Department to drop an antitrust investigation of British Airways as a personal favor to “Maggie” (as he called her in private). The special relationship is messy and uneven — at times, it seems little more than a fiction. Here’s hoping Aldous turns next to an account of the Bush-Blair years.